I distinctly remembered feeling anxious a little more than seven years ago as I walked through the parking lot at a Northwest Side assisted living facility. A queasy feeling hit me just as I passed through the front door.

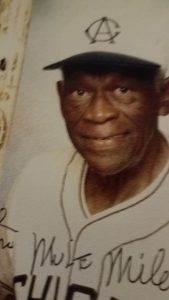

San Antonio’s John Miles played for the Chicago American Giants in the Negro Leagues from 1946-49

On assignment to interview former Negro League baseball standout John “Mule” Miles, I knew that Mr. Miles, at age 90, wasn’t feeling well. I knew it might be our last conversation. Nevertheless, my assignment from a trusted editor at the San Antonio Express-News was clear.

I had been asked specifically to explore how Miles felt about the social injustice that made it necessary for black ball players to play in one league and whites in another, for so long.

Having interviewed Miles a few times before our last meeting in April of 2013, I knew that he had deftly skirted some of those difficult questions in the past.

From the day I met him in the early 1990s, he exuded positive vibes and loved to talk baseball, but “Mule” had always stopped short of expressing his most painful feelings on the subject of race.

He was charismatic. Charming. Gracious. But never really forthcoming about his own personal journey.

So there I was, standing at the reception desk at an assisted care center off Huebner Road, and my stomach was in full churn. The last thing I wanted was for Miles to feel uncomfortable with my line of questioning.

Not this time.

Looking a little frail, Miles invited me into his room with a welcoming smile and took a seat. I took mine. As the afternoon sun splashed through the curtains, we started to talk, and it was pure gold.

We talked about Jackie Robinson. Satchel Paige. Josh Gibson. Oscar Charleston. We talked about Miles’ best friend, Clyde McNeal, his boyhood pal from San Antonio and a flashy shortstop with the Chicago American Giants.

Miles had always been so grateful for McNeal’s friendship.

In 1946, McNeal talked Miles into leaving his job as a mechanic at Kelly field to take an offer to play for the American Giants, where they remained as teammates for a few years under manager “Candy” Jim Taylor.

The friendship continued for decades, until the end of McNeal’s life, when Miles would help transport his wheelchair-bound friend to some major-league cities, to attend some of the celebrations of former Negro League ball players.

We had talked about all of that. But, never had we really got down to the nitty-gritty on how he felt about discrimination. Until our last meeting, when it all poured out of the old ball player, perhaps because he sensed it might be the last time to get it off his chest.

I remember sitting there, stunned, as Miles started to talk about 1942 and his trip to Tuskegee, Ala., to work as mechanic trainee with the famed Tuskegee Airmen.

The Tuskegee Airmen were American heroes. A World War II fighting force. But Miles said he remembered one incident when he didn’t feel like a hero.

“I’m in my car with Texas plates and driving 20 miles per hour,” he said. “I said, ‘Oh, my goodness, the law is behind me.’ ”

With his pregnant wife in the passenger seat, Miles pulled over, and the officer approached on foot holding a gun, talking about how a tail light needed to be fixed.

“He says something, and I say, ‘I beg your pardon?’ ” Miles asked. “And then he said, ‘Oh, you’re one of them smart ones.’ Then that guy doubled up his fist and hit me, knocked my baseball cap across the window.”

Miles said he didn’t retaliate because he remembered what his mom and dad had told him before he left Texas.

“My mother and father taught me how to act,” he said. “They said, ‘You don’t get ugly, because if you do, things happen, and they happen real fast.”

About a month after my story was published, John Miles passed away.

The likeness of native Texan Biz Mackey, an Eagle Pass native who grew up in Luling, adorns the official logo of the Negro Leagues centennial.

I wanted to share it with everyone today because, No. 1, this is the centennial year of the Negro Leagues. No. 2, because guys like Miles and McNeal never really received the credit for their athletic success. And, No. 3, because of current events.

In exploring Miles’ experience with law enforcement in the South in the 1940s, maybe we can begin to understand why so many remain so frustrated with the system more than 70 years later, in the wake of George Floyd’s death.

Like Miles, Floyd was an athlete from Texas. Miles grew up in San Antonio. Floyd in Houston. Miles survived racism in the 1940s and lived a long and mostly happy life. Floyd, who attended Houston Yates High School in the early 1990s, wasn’t nearly as fortunate.

He passed away on May 25 in Minneapolis, with an officer’s knee on his neck, setting off waves of protest in the nation. Knowing Miles, he no doubt would disapprove of the violence and looting plaguing American cities for the past week.

But knowing how it feels to be targeted, I am certain that he would feel sympathy for those who are offended and angry with a system that continues to yield bad results for minorities.

It is a galling reality that, all these years later, should make everyone feel a little bit queasy.