By Jerry Briggs

An in-depth report, for The JB Replay

About 35 years have passed since a World War II-era baseball ambassador named George Ligon, Jr., died and was laid to rest in Southern California. A headstone at the man’s Brawley, Calif., gravesite marks his service to the nation as a U.S. Army veteran of the war’s Pacific theater.

George Ligon, Jr., started a touring baseball team out of Hondo in the 1930s. It played in the United States, Canada and Mexico for 15 years through the early 1950s. Ligon kept the team going even after he returned from military service in World War II. Photo copy, from the archives of the Brawley (Calif.) News.

Another memorial dedicated to him also can be found in South Texas, about 40 miles west of San Antonio, in an out-of-the-way, rural cemetery where visitors can hear the wind “rattle” the seed packs in the thick brush.

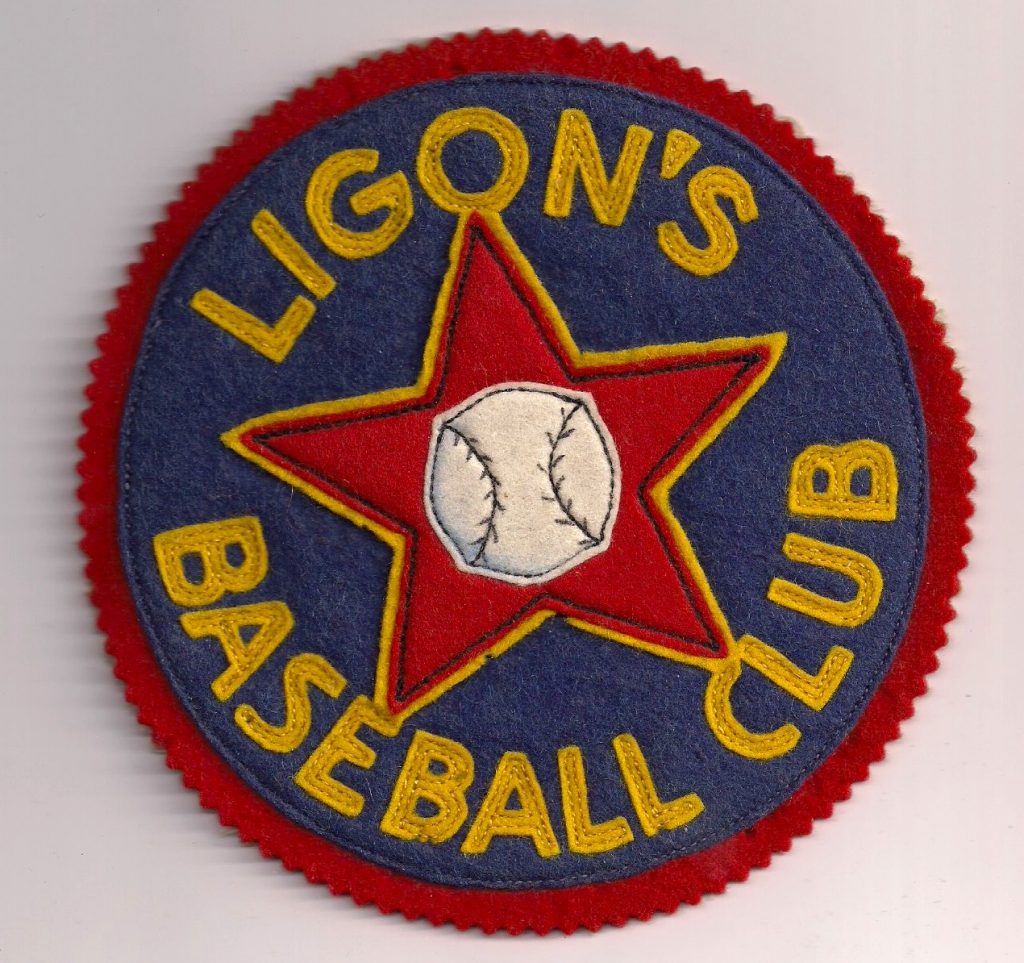

In the small town of Hondo, Ligon served honorably in the world of sports. He was the founder and proprietor of “Ligon’s Baseball Club,” a black touring squad that traveled by bus to play games in 20 U.S. states and in three countries over a 15-year period through the early 1950s.

Appropriately, a marker at the Cottonwood Cemetery in rural Medina County is adorned with the team’s red, white and blue logo. A white ball, inside a red star, on a blue background. Clearly, the man loved his team, and he also loved his country, despite all of its flaws in the Jim Crow era.

“This is really the story of America,” said Laurence Ligon, a Maryland resident and the son of the man who ran the ball club. “It’s really our story. It’s not just one (racial) group. It doesn’t belong in one (category). It’s really everybody’s story.

“Because, for my father, one of the things that I can say, for all the slings and arrows that got thrown at him, he didn’t have (the capacity) to hate people. Or attack people. Or be angry with people.”

It’s a timeless lesson that is relevant today, even though George Ligon, Jr., was born in Texas in 1910 at a distinct disadvantage in society.

Regardless, the son of an Austin-area farmer soon started to make a name for himself, first as a baseball pitcher in Uvalde and then as a Hondo-based player/businessman whose enterprise gave others an opportunity to showcase their skills.

“At first,” George Ligon, Jr., said in a 1982 newspaper interview, “my brother (Rufus) and I played for a white fellow who owned a black team, and we played against white teams quite often.”

But, not always, because inter-racial games were controversial at the time. He told reporter Peter Odens of the Brawley (Calif.) News that the black teams in the area just couldn’t make it in a league of their own.

Owners of the white teams owned the ballparks, Ligon told Odens, and those owners charged the black teams 45 percent of “the total take” to play on their fields.

“It was a good league while it lasted,” Ligon told the newspaper. “Anyway, I started my own team in about 1937 and made it a traveling team. Had it for 15 years.”

Laurence Ligon said in a telephone interview that his father managed the team and drove the bus on trips that started in Hondo, led into the Midwest and then veered into the Rocky Mountains and Canada.

Later, the All-Stars traveled down the West Coast – and into Mexico.

“My dad told me some of the craziest stories,” Laurence Ligon said in a telephone interview. “Like, the brakes on the bus fell out. (Then) they … over-heated. And they ran the bus into a hay bale. And the farmer came out, and they had to help him re-bale the hay.

”I mean, all kinds of stuff like that. They were just (out there) running around on the plains.”

Because of all the time that has elapsed since this epic baseball venture began, a lack of first-hand information keeps anyone from knowing exactly how the team got its start.

For instance, what was the nature of the bus and the travel? When did Ligon buy the bus? It’s possible he purchased it in the 1930s because, during the Great Depression, many commercial bus companies were going out of business in the economic downturn.

Which leads to the possibility that Ligon could have negotiated a bargain buy at that time. If he didn’t, then it’s also plausible that maybe he just had to wait until after he returned from fighting in the Pacific theater of the war.

Maybe he finally made enough money in the Army to save up for the purchase. If that’s the case, then it was a high price to pay, because Laurence Ligon said he believes his father was wounded while fighting in Buna, on the island of New Guinea.

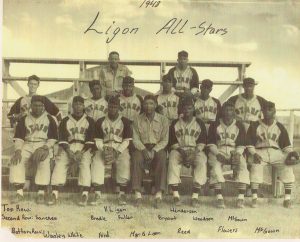

A team picture of Ligon’s Baseball Club. Photo, courtesy Laurence Ligon

The battle of Buna-Gola, according to historians, was a bloody, three-month jungle fight that started in November of 1942 and ended with an Allied forces victory in January of 1943. Many of the soldiers who survived came home with malaria.

“I don’t know if he volunteered or if he was drafted (into the Army),” Ligon said. “But he went to train at Fort Huachuca (Arizona). Then he went and fought against the Japanese and was wounded, somewhere in the islands around Guadalcanal. I think it was on Buna.

“So, he was discharged, came back, and, from like 1947 to ‘50 or ‘51, they were still traveling (with the baseball team).”

Apparently, Ligon wasn’t the only member of the All-Stars with a hard-scrabble background. A search of archives in the Hondo Anvil-Herald turned up information pointing to how Ligon assembled his team in the late 1940s with prospects who had known each other for years.

Several apparently first attended the town’s segregated school for blacks. When the Anvil-Herald in 1998 ran a story on a Ligon family reunion, it also published what was labeled as a 1939-40 class picture of the Hondo Colored School.

Included in the picture were students identified as Cleveland “Babe” Grant, Sterling Jasper Fuller and Roy “Banky” White. In a separate issue of the newspaper published to commemorate local World War II veterans, Fuller’s name was on the list of those who served.

The names of Grant, Fuller and White, in turn, were listed on baseball websites that chronicled the Ligon All-Stars’ games in Canada in the late 1940s and early 1950s. Meaning that, the players on those long bus rides out of Hondo, to Canada, and back again all shared a unique bond.

Some of them likely were neighbors as kids. Maybe a few of them walked to grade school together. At least one (Fuller) served in the military and all of them, to a man, loved to play the game – no matter what. They’d travel for hours on end knowing that, in some places in America, they just weren’t welcome.

“You have to know where they don’t want you (to play), and then … don’t play there,” recalled George Ligon, Jr., in the 1982 edition of the Brawley News.

Laurence Ligon, 60, a California native who lives in Maryland and works in computers, said he didn’t know much about the All Stars until a reporter showed up at the family’s home to interview his father in the early 1980s.

“I had heard some of those stories, but (with) the guy asking some pretty good questions, they sat there and talked for a good five hours,“ Ligon said. “And I started hearing a lot more about it.”

On and on went the conversation.

“I was blown away,” Laurence Ligon said, recalling the day his father laid it all out for the visiting reporter. “I just didn’t know that my dad had done all that.”

Ligon said he sometimes jokes about his “gypsy” heritage with friends and family.

“I tell guys, ‘That’s where I get this gypsy blood of mine,’ “ he said. “I love getting in the car and traveling. My dad drove the bus. He managed the team. He drove that bus from Hondo all the way up to Saskatchewan.

“Then they’d come over and play in California and go down into Mexico and play, and then head back to Hondo.”

In 1947, Jackie Robinson made headlines around the nation and changed the game when he broke the color barrier in the major leagues with the Brooklyn Dodgers. Around the same time, the Ligon All-Stars were putting in almost 200,000 miles on their bus over one four-year stretch.

Ligon’s Baseball Club would hit the road in a bus for trips that would carry them thousands of miles. Photo, courtesy Laurence Ligon

All the while, playing in front of some white fans who perhaps had never seen a black athlete on a baseball diamond. Cutting up. Having fun. Sometimes playing with a catcher who would tease the crowd by sitting behind home plate in a rocking chair.

“I have heard about that one, yes,” Laurence Ligon said with a laugh.

One day, Ligon said he hopes to return to Hondo to have some work done on the exterior of the old cemetery. He said he wants to preserve the peaceful setting, in a rural area a few miles north of Interstate 90, with head stones dating back to the Civil War.

“It’s a really nice (place),” he said. “I don’t know what (kind of) plants they have (on the grounds, but) I remember they’re like a bush, and at the very top (of the plant) it’s kind of heavy. They’ve got like a seed pack on the top, and when the wind blows, these seed packs kind of rattle.

“It just makes this really calming sort of noise. I go out there and I just want to sit down and just kind of take it all in. It’s really beautiful.”